|

One of these things is not like the others, One of these things just doesn't belong, Can you tell which thing is not like the others By the time I finish my song? OK, OK- actually NONE of these are like the others. At first glance all of these wash dresses look very similar to each other. HOWEVER, on close examination it will become obvious each was made in a different time frame. Everyday dresses such as these can be especially hard to discern time frame because they don't obviously show things you might have seen in fashion magazines. To date them you need to go back to the very most basic of patterning rules for that particular period. In this blog post I am going to attempt to show you some of the things that might fool you into placing them in the WRONG time frame, as well as some of the things to look for to make sure they are placed in the RIGHT time frame. Are YOU ready to play Dress Detective? We will start from left to right and examine each dress in detail. I'm going to tell you a bit about each dress, then give you a date and tell you how I arrived at that time frame. Click on photos to enlarge them.

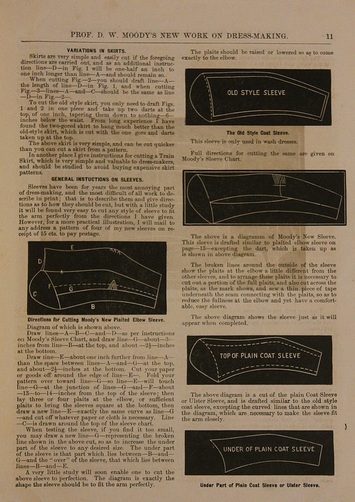

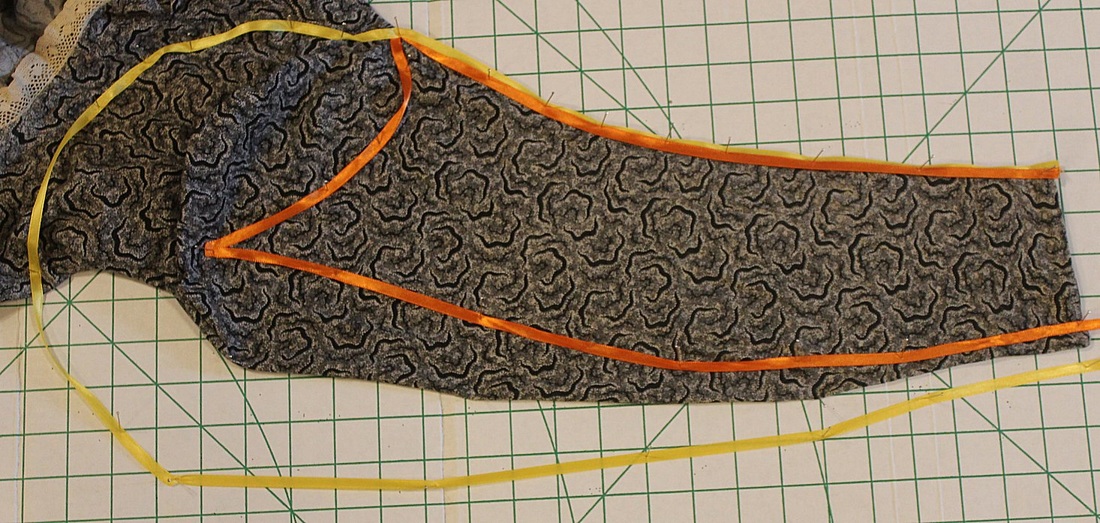

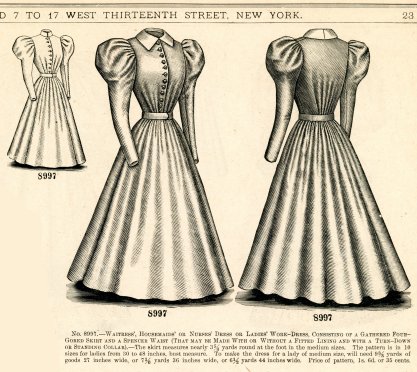

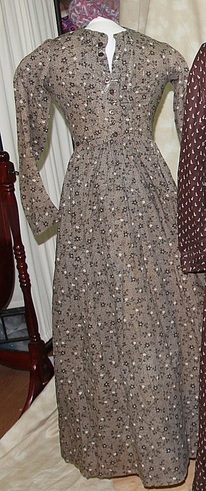

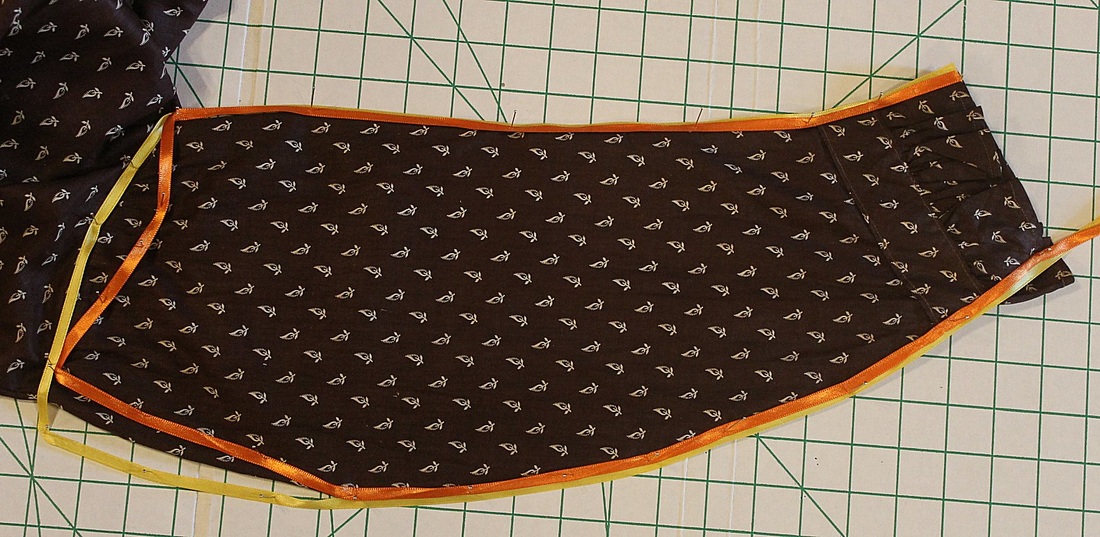

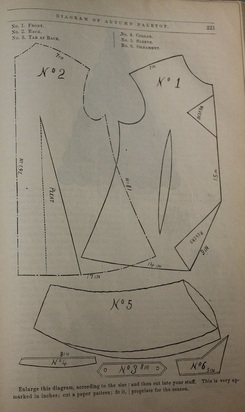

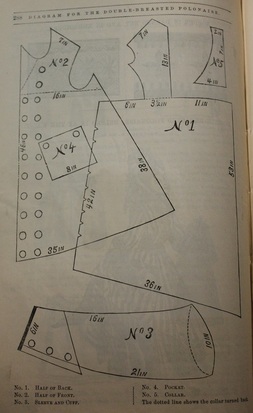

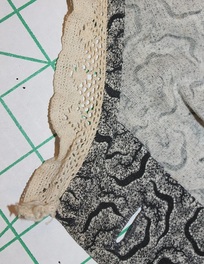

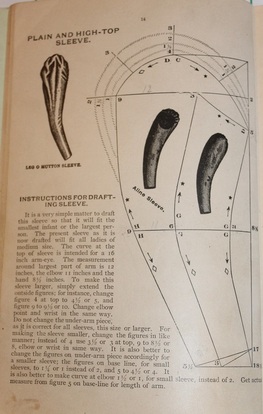

To help you see the sleeve patterning, I have carefully pinned ribbon using fine silk pins along where the seamlines would lie. The orange follows the under piece of the two piece sleeve, while the yellow ribbon shows where the upper pattern would look like if it were unpicked from the armscye and the under sleeve piece. Have you made your guess on this dress? I date this dress to between 1882-1885 My reasoning: The basic pattern for the bodice could place it anywhere from the early 1880's to the 1890's. A separate underarm piece started appearing in fashions from the very late 1870's, but by the 1880's it was firmly ensconced. Look first at your bodice seams when dating a dress- when photographing it opening it up where you can see all the seamlines clearly is a definite plus when someone is attempting to help you date a piece and can not be there in person. The tucked or as the 1882 Butterick catalog calls it "plaited" waist was fairly popular, and fits well into my original estimate.  The sleeves and shoulder length are your other big clue. The shoulder length is very short which means it has moved past the late 1870's and well into the 1880's when the armscye was closer to the hinge point of the arm rather than the outer shoulder as it had been just before. To accommodate this shorter shoulder the sleeve patterning had to be changed to add more fullness to the sleeve cap. The top of the sleeve is eased into the armscye, leaving only a few small wrinkles but no real fullness or gathering. By 1886 most dresses were showing more fullness at the shoulder with at least a slight gather so I am placing it before this time frame. The image at left shows Professor Moody's sleeve pattern from 1885. The "old style" coat sleeve is one in use from the late 1870's through the early 1880's.  These are two sleeve patterning systems from the same maker at different dates, Both William's Perfection system. The one on the left is 1879 while the one on the right is 1885. You can see how the sleeve cap portion is starting to grow higher as the armscye moves up the shoulder. Did you guess the same? Some of the things that might have thrown you off are: 1. No collar. Most people think of 1880's dresses as having high collars. IN reality 1880's has more styles of collars, heights of collars and collar attachments than any other time frame I study regularly. You may see wash dresses with no collar, fold over collars, shaped stand up collars, or curved patterned stand up collars. 2. Skirt attachment. In the 1880's there is a wide variety of ways skirts are attached, everything from stroked gathers, to gauging, to pleating. 3. No overskirt. Fashion plates of the 1880's tend to show longer waistlines and overskirts. Remember wash dresses and work dresses aren't going to look like fashion plates except for bare bones of the seamlines. 4. Dog-leg waistline opening. Sometimes people automatically think civil war era when they see a dog leg opening (where the bodice opens down the front but the skirt opens to the side front at a seamline) This style of closure can be found into the 1900's and really depends on the seamstress.  Dress #2 Chocolate brown cotton print lined with a fine brown twill. Hem circumference 104" -5 panels of 23 inch wide fabric Skirt has 2 full back panels, two gored side front panels (8.5 inches at top and 16 inches at bottom), and a gored front that is 23 inches at the bottom and 17 inches at the top. Shoulder length is 7 1/2 inches and there is a fine self piping at the armscye and a heavier self piping at the bottom of the waist. The dress is mostly machine sewn with a chainstitch machine. There is a note pinned to this dress that reads: "note of mother,I think she made this dress before I was born about 1883 she was tall."  It has functioning black glass buttons. (button and buttonhole closure) Shoulder length is 7 1/2 inches and there is a fine self piping at the armscye and a heavier self piping at the bottom of the waist (shown left).  The bodice has a back with a center seam, and the front bodice piece extends to the back of the dress forming a curved seam at side back. (note the spliced in fabric on the lining to get enough width. Center front opening in the skirt that has been slashed and turned back under to form about a half inch placket. (no separate placket pieces sewn on) A topstitched pleat at the bottom of this placket reinforces it.  The collar is about one inch tall and "mandarin" style- not meeting in the front and curving off slightly at the top. The collar is applied both sides at once and the the raw edge on the inside is covered with self bias. Have you made your guess on this dress? I date this dress to between 1870-1874 My reasoning: Let's start with the cut of the bodice. The lining is fitted with darts and seams to the waistline while the outside has slight gathers to fit it to the waistline. We first look at the cut of the lining. If you drew a line to just the waistline you would see the cut is VERY much like the 1873 polonaise below right. The front bodice extends toward the back, and the back is cut with a center back seam and fairly wide at the bottom. The sleeve style is very close, but even closer to the pattern below left on the paletot. The applied ruffle and band on the sleeve is very common in the early 1870's through about 1877 on wash dresses. Notice that the upper and under sleeves are much the same shape- a fairly wide coat style sleeve. Because the armscye on an early bustle dress extends to the edge of the shoulder, you do not need the higher upsweep in the sleeve head to accommodate the upper arm. Another clue on this dress is the chainstitch machine stitching. Chainstitch machines are one of the early styles of sewing machines- as a general rule I see chain stitching on early bustle dresses and before- BUT this is not a hard and fast rule, there will be exceptions. The use of heavier piping at the waistline. Where fine piping for strength was the rule in the 1860's the 1870's sometimes made it heavier and used it for its decorative function. The Sylvia Koester dresses from 1875-78 in Manhattan Kansas have some great examples of this. The facings on the fashion fabric turn back separately from the lining fabric. (there is a gap between the lining and the fashion fabric at front between buttons/buttonholes) I have another dress from the early bustle time frame that has this feature as well. Did you guess the same? Some of the things that might have thrown you off are: 1. Stand up collar. Refer to my collar comments on the first dress. A stand up collar is a perfectly accepted style for the early 1870's, it will likely be an inch tall or less- 2-3 inch collars are usually late 1880's into the 1890's 2. Skirt attachment. Most people think civil war or earlier on the cartridge pleated, folded over top that this dress shows. I have dresses as late as the mid 1880's with this style of skirt finish/attachment a the top. 3. Sleeve piping. You might guess it is earlier(1860's) from the fine piping at the sleeveline, however the cut of the bodice lining and the heavier waistline piping push it to a later period. 4. Gathered front and back fashion fabric. Without seeing the fitted lining this dress might fool you into thinking it was from an earlier era. The lining pattern tells the true period of the dress.  The skirt is neatly gathered by hand and attached to the bodice with a machine stitch.  The upper and under sleeves are fairly slim and are much the same shape with the exception of the slight taper of the undersleeve at the top front.  The collar is a straight of grain folded over band about an inch wide finished that is machine sewn over the raw edge of the neckline.  1879 dressmaking system Back/sideback and sleeve patterns 1879 dressmaking system Back/sideback and sleeve patterns I date this dress to between 1874-1877 My reasoning: By 1874, while the sleeve shape at the top had not changed much, it was starting to slim down from the fuller style of coat sleeve of the early 1870's. The shoulder length was starting to become a bit shorter as well, but it had not yet hit the point where you needed a higher sleeve cap to accommodate the short length of shoulder seam. This dress does not yet show the underarm seam or dart that would become more more popular as the dresses were fitted tighter and lower to the form. The sideback form still curves to the armscye- sometime in 1876 you see the appearance of the side back form extending instead to the shoulder line, but by the early 1880's that had mostly disappeared. The textured fabric found in the lining was also something that seemed to be was popular in mid 1870's. This dress has no piping at waistline or armscye and the sleeves are put in by machine. Dresses made more on machine were losing armscye piping by around 1874. By 1876 piping was usually no longer a reinforcement, but instead a design/decorative choice. Did you guess the same? Some of the things that might have thrown you off are: 1. Mostly Machine stitched. By the mid 1870's MANY of the everyday dresses you see have very very little handwork in them. Buttonholes are still made by hand, as is much of the gathering for skirts, but a hand stitched dress has become the rarity rather than the rule. Because of the amount of machine stitching you might guess later. 2. Short front waistline. When I drafted this dress out for Domestic Lady's dressmaker I was very surprised to realize that it actually scooped up at center front bodice. By all appearances this was likely a maternity dress. The small upward sweep in the front would allow the fullness of the skirts to hide a rounding belly that might otherwise be starting to be obvious in this fashion time frame.  Bodice pattern piece include Back with center back seam, side back curving to armscye, and Front with dart from armscye to waist forming underarm piece.  The Sleeve is much fuller than it first appears to be when it is pinned out on the board. The high sleeve cap line was measured and extended by ruler while placing the pattern line because fuller sleeves are harder to pin flat at the upper edge. I date this dress between 1893-1898 My reasoning: There are a couple of things going on here- first and foremost are the sleeves. Sleeve patterns didn't really reach the shape shown on the dress until about 1893. The sleeve patterning system on the left below is from 1892- you can see the sleeves are becoming fuller, but were not "quite" there yet. On the right below is the Square Inch Tailor system published in 1900, just before the sleeves would collapse again. The shape is very similar to our sleeve on the dress, and would first be seen about 1893. Also notice that the shoulder seam length is very short- this is an 1882-1902 trait. The number of pieces in the bodice are another clue. The extra "dart" that forms an underarm bodice piece, gives you the standard bodice shape from about 1882-1902. The fact that it extends past the waistline point makes it more likely to be 1890's than early 1900's as bodices were more likely to end at natural waistline from about 1899 onward. Something that is harder to tell from the photos is the fabric itself is also not as high a quality as fabric from earlier eras. The weave is not quite as tight and the fibers are not as durable. Cheapness of fabric allowed for interlining the bodice with self fabric, but it also showed as the bodice has split along one of the front bust darts from strain.  Did you guess the same? Some of the things that might have thrown you off are: 1. It's hard to see the sleeve fullness on the mannequin. Honestly, I didn't mount these pieces "properly" before photographing them for this blog post on purpose. Most of the time when I see people asking "What time frame is this dress?" it is draped on a bed, put on a ill fitting mannequin and without any inner bodice photos. As you may have noticed I rely heavily on prevailing patterning trends to help date tricky dresses, and sleeves are one of the points that can make or break support for a certain date. Some fine silk pins and a cardboard cutting board can really help your dress identification process. 2. Collar height. We expect collars from the 1890's to be very high from most fashion plate images. The image from the 1897 butterick catalog for a work dress shows, both a stand up collar and a fold over "shirt collar". Some dresses from this time frame have nothing but a bias binding at the neckline. Trying to date a dress only by the collar style can easily lead you off track. So, how did you do? I hope you enjoyed my little game. I have been studying Victorian and Edwardian dress for many years, and when my interest turned early on to everyday clothing I knew fashion plates were going to be of little help to me and started my two favorite collections. Butterick pattern catalogs and dressmaking systems. Using these two collections my third collection- extant Work/At home/Wash dresses started to make more sense to me. The more original pieces that came to be in that third collection, the more I realized what things covered larger time spans than I originally realized, and what would help place a dress in a specific time frame. For example, my current opinion is there is no wrong way to attach a wash dress collar from 1870-1900. I have seen nearly every way possible in nearly every fashion period in that timespan to the point there are very few collars I would call out as specific to a time frame. (There ARE some- but that is another lecture.) With the advent of reasonably priced paper patterns in the 1860's, and fashion magazines publishing patterns within their pages, most women had access to current basic pattern shapes for bodice and sleeves. ALL images in this blog post are from my personal collection. Please do not copy and use as your own- but feel free to share the blog post as much as you like. If you would like to study some basic patternmaking guides without starting your own collection

you should go browse archive.org The science and Geometry of Dress -1876 (slightly old fashioned as the new pattern cut was just appearing) Instruction Book for the French and English Systems of Cutting Fitting and Basting-1881 You have to flip through the whole book to see that 1881 was a pretty transitional year and several cutting styles were being used. A System for Cutting Ladies Garments- 1883 Directions for Cutting Garments with the Improved Davis Square-1888 The Scientific System of Dress cutting- 1894 There are Many many more- try searching dressmaking or tailoring and select by date published early to late.

3 Comments

|

AuthorPainfully obsessed clothing historian, Archives

January 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed