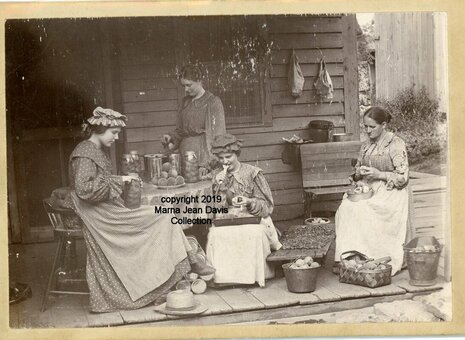

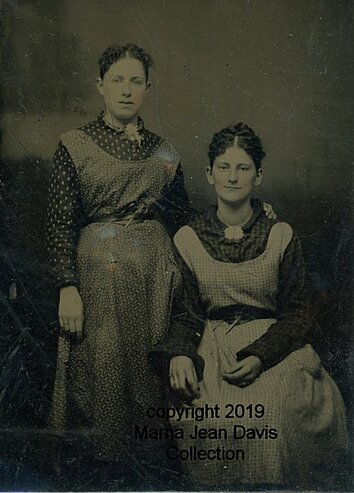

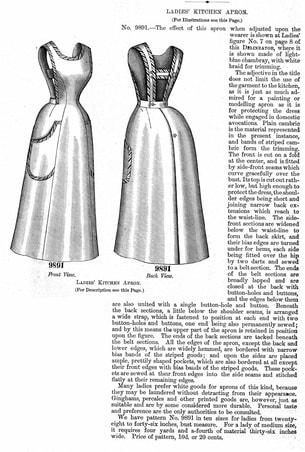

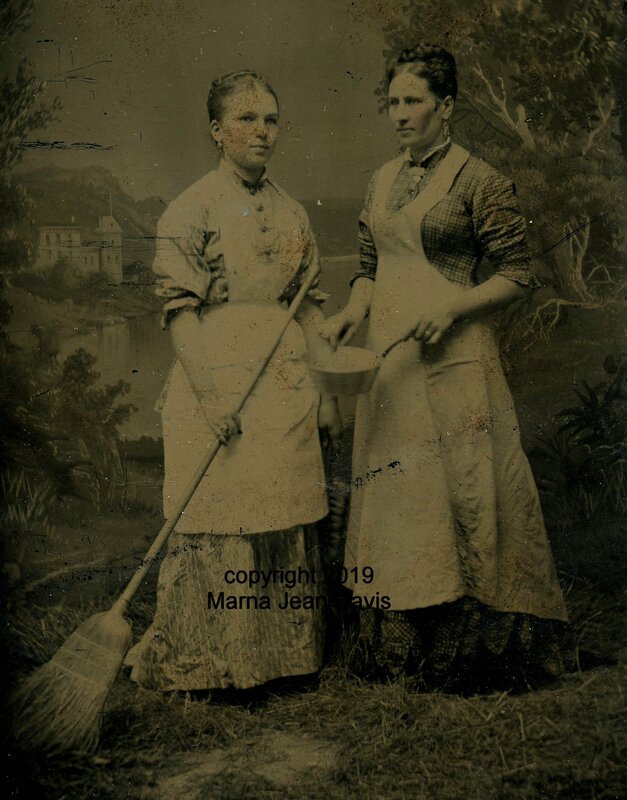

One of the challenges of putting together copy and research for an exhibition is, you can't turn it into a book, it is meant to be a quick learning experience to inspire you to find out more. I decided for those who want a "bit more" I would blog about some of the reproduction aprons we used (the light level is too high in the area for originals) and a bit more about the dating and history of some of the images.  As you enter the exhibit this image is featured. This is 1890's and seems to be ladies canning peaches. The aprons here are pretty typical of late Victorian everyday wear aprons. A simple long rectangle gathered to a waistband that covered most of the skirt. I could imagine this happening on the porches at Nash Farm when I acquired this image for my collection. Many of the original aprons like this I have seen make use of selvage edges as the sides of the apron, leaving two less hems required when making an apron.

By the needlework panel you will find a knitting apron. This was modeled after an original in my collection. It is meant to be a portable "pocket" that holds your needlework or knitting. If you have to put it aside to tend to another chore, simply remove the apron and it is all neat and tidy for the next spare minutes. The original apron is a white barred cotton. The strings are not made long enough to tie, but instead would pin together. I chose slightly wider ribbon on my reproduction and a sheer ivory barred fabric. I hope you get a chance to visit Grapevine and see the exhibit and stop by Nash Farm and say Hello! below are a few images of me and my visit to the finished exhibit. Views from Grapevine, TX- Aprons of the Past

1 Comment

Blevins buckles and a breast collar ? And you are supposed to be an 1860's man! Blevins buckles and a breast collar ? And you are supposed to be an 1860's man! I’ll admit it- the discussion that ensues during most late 19th century historic films in our home would drive most people to madness. Never mind the hero of the movie has been shot, is lost, out of ammo and the girl still hasn’t been rescued. NO we are exclaiming things like “WHY did they put a 1940’s saddle and gear on that horse, isn’t it supposed to be 1870’s?” And did you SEE the neckline on that dress for day? And in PUBLIC? That girl would have been shamed into propriety by the town ladies AGES ago.” OH we realize it’s just a movie, BUT THEN we go to the museum or reenactment events and see those folks who have done their research “via film” and are mis-representing the past, and the domino effect goes on… We HEAR the mom whisper to the child, “Look, this is just like they did it in the olden days!” It makes us sad. Film I can forgive as artistic license. However, when I walk into a museum that has not done a good job of research and representation of a time period, it makes serious shudders run up my spine and my stomach go all wobbly. As the keepers of our history, museums should be held to a higher standard of correctness. Simply by being in a museum display the item now carries “weight” as history. This is where the importance of being earnest comes in. Earnest is defined as a noun as “full seriousness, as of intention or purpose” and as an adjective as “serious in intention, purpose, or effort; sincerely zealous” or “seriously important; demanding or receiving serious attention.” History in a small museum can be HARD! Many of them were begun around the time of our nation’s bicentennial by enthusiastic citizens who only had their stories, and their parent and grandparent’s stories to guide them. While oral family histories are a good place to start, any competent detective will tell you memories are easily contaminated through discussion and re-telling. Good research needs to be a part of verifying artifacts, especially those used in displays. The world is becoming a more visual place all the time, and so the visual aspect of an exhibit bears serious consideration.  Some of my Grandma's 1940's quilts. Some of my Grandma's 1940's quilts. Grandma’s wool quilt she made in the 1940’s becomes the one that Great-Great Grandpa carried during the civil war. To a practiced eye this unintentional misinformation can be easily ferreted out, but convincing the family of it may be another thing altogether! Another issue in many small museums is that the accession records really have very little useful information to the historian. “Beaded moccasins donated by Mrs. B in honor of her son” might be 1880’s brain tanned Sioux, OR they might be 1940’s made for trade. Other than showing the donor, no other info is given. Until recently it has been hard to even start to properly label items, but with the internet, access to good research has become so much more available. Amazon can be used to not only look up identification books, but see other’s reviews of those books. As a professional, my personal library is massive and there are always new books on my “want to buy” list. Facebook offers many groups with specific areas of study that can often provide a good lead on where to research (ALWAYS ask for sources to read when dealing with facebook!). Networking of historians with specific interests can ease the burden of having one person having to “know it all”. Personally, I have a group of friends that I know to be well versed in areas that I am weak in. These are the people I can rely on to ask, “What is this item and where do I go to learn more about it?” I hope they feel they can do the same with me in my own specific concentration area of study. Many large museums with funding and better access to experts in specific study areas have put collections online and can be a great help for the local museum in doing beginning research for their collections. This does not mean they are necessarily infallible. I have seen mis-dated clothing items in online galleries as big as the Met, although those are few. So EVEN realizing the challenges presented to smaller museums for identification, I still expect earnestness. When putting together an exhibit centered in the 1870’s using a 1930’s candy store jar with its bowled base and aluminum lid is nothing less than lying to the public. Simply putting something in an exhibition because it looks “old fashioned” and “We already have it” is not good enough. By doing so we are, in fact with our own full knowledge, re-writing history. Our viewing public is generally innocent as to knowledge of artifacts. We must in “FULL SERIOUSNESS” attempt to present as accurate a picture of the past as we possibly can. This sometimes means admitting we do not know everything and asking for help, and it sometimes means removing an item from an exhibit that skews history. Sometimes it means relying on well done reproductions to fill in gaps in the museum’s collection to give the public a visual that they can relate to more concretely. This may mean weeding out the 1920’s graniteware from the 1880’s graniteware and putting each in the exhibit where the time frame makes more sense. Sometimes it is making a tough call knowing someone will be sad, hurt or angry because an artifact has been moved or removed from an exhibit, but our responsibility to our ancestors and our history remains above all lesser concerns. A museum’s job is to PRESERVE history, even with its flaws, not to re-imagine it to our own whims. Many treasures with important stories can be discovered in small/local museums, and the public needs to be able to trust in the museum for accurate information. Museums should be a place to invoke a curiosity of the past, but one should not come away from them having learned incorrect information. In my personal collection at home I have the advantage of being able to talk to every viewer of my artifacts from spinning wheel to arrowhead, and day dress to shoemaker’s tool.

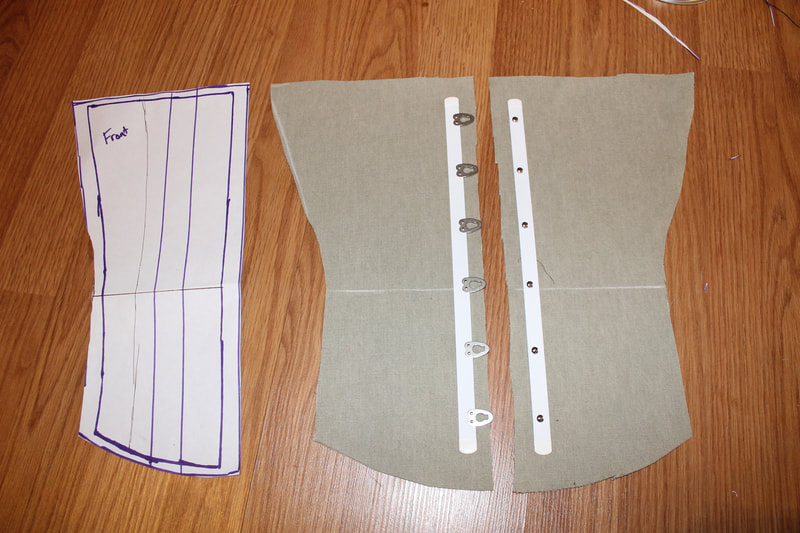

A museum’s displays have to speak for themselves. Are yours representing your history earnestly? Or are they whispering falsehoods to the public?  Some time back I created a museum exhibit for the Chisholm Trail Museum. The display was called "No Lady of Leisure" and it featured some of the work dresses and wrappers from my personal collection. The problem was the small museum did not have enough display pieces for the dresses and the ones that they did have were entirely too large for most of the dresses to fit without causing strain. We started pricing mannequins and display pieces to realize that the cost was going to be extremely prohibitive to properly showcase more than a dress or two. I needed a way to be able to display more than a dozen dresses at a reasonable cost for a short term basis. After a couple of adjustments I created a display mannequin that was small enough to showcase my dresses, had a general form similar to a corseted body, and was fairly cheap to make. The pattern features easy to obtain materials, is quick to make and has built in shoulder/upper arm support. The Bust measure is around 30" and waist around 22" depending on how firmly it is stuffed.  I have now released the pattern I developed to the public. To assist museums and historical sites with their never ending budget crunch, this pattern is free by request to non-profit organizations Please email me your: name, museum name, address, and email- I will email you back a PDF copy of this pattern. For personal use I have made the pattern available in my etsy shop as a digital download for $5. |

AuthorPainfully obsessed clothing historian, Archives

January 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed